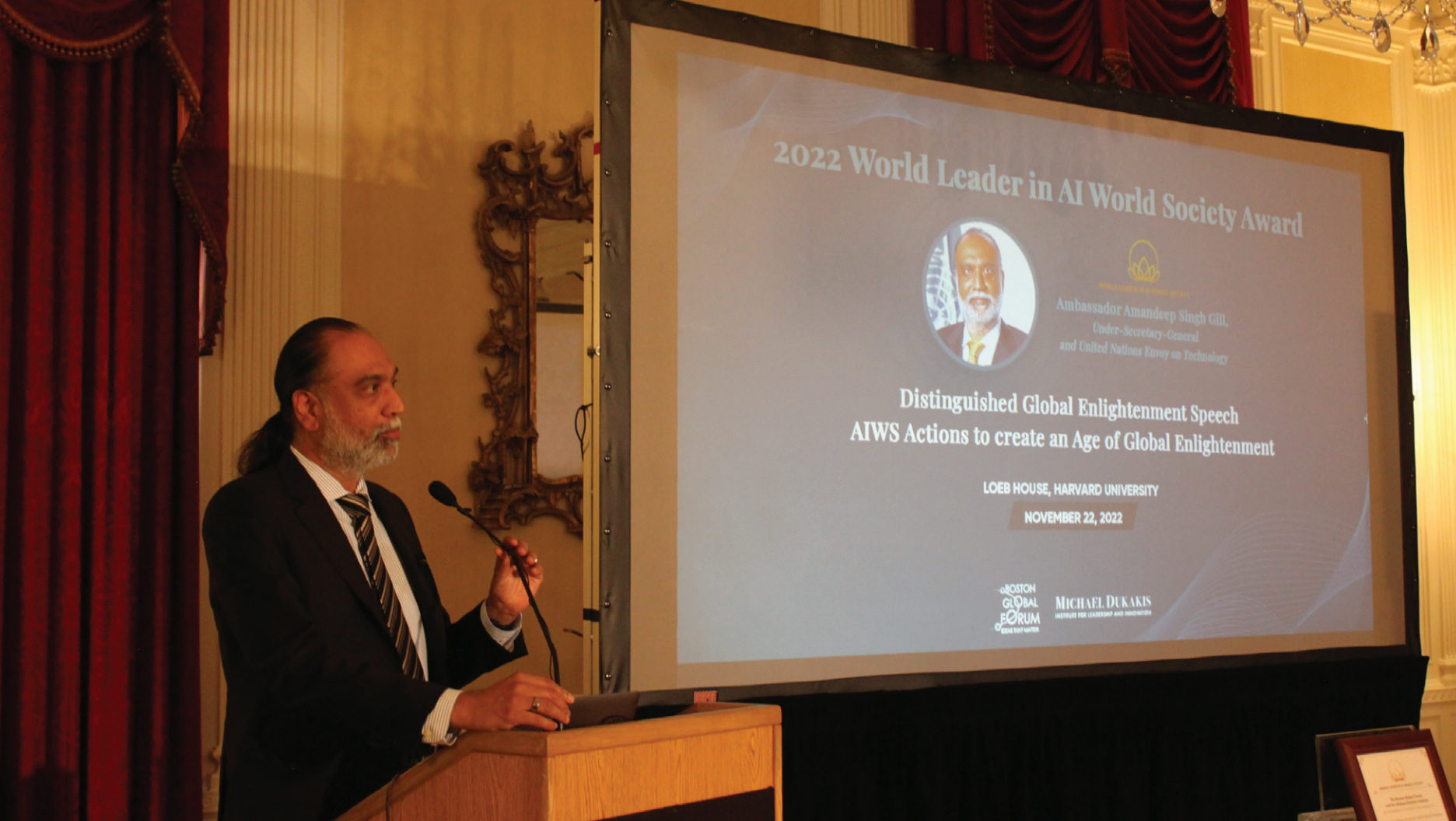

Here is transcript of the Distinguished Global Enlightenment Speech 2022 of Ambassador Gill, please see video to get full of his speech: “Thank you very much for honoring me today. Dear Tom, Tuan, ladies and gentlemen, It’s a pleasure to be here at Harvard to spend some time with you and talk about digital technologies and the issues that they pose for our societies, our economies, and our political systems, whether national or international. I’m deeply honored by this award, which I think should rightfully go to all those who are toiling away in our academic institutions, in multi-stakeholder forums, in multi-sectoral forums to get a better understanding of the impact of these technologies across the three pillars of the UN—- Peace and Security human rights, and of course development, and are working together, often unacknowledged, often in obscurity to reinforce international cooperation around these technologies. Powerful technologies have been around for a while. We have in the 20th century dealt with the power of fission and fusion, often not in very successful ways. We’ve dealt with space technologies. We can envision technologies coming from the biological domain. What is perhaps different is that digital technologies are coming more and more from the private sector. Their development has not been shaped as much by government intervention or by public institutions, as has been the case with other powerful technologies. The other thing that we must keep in mind when we talk about digital technologies and Artificial Intelligence Systems (AIS) is the way in which they cross borders. They have transportability, in fact, like no other technology does. So, a small app in a remote location, if it is the right kind of moment, the right kind of user interface, can scale to global proportions in no time and reach anywhere and, through social media platforms, through other digital means, impact the consciousness of billions around the world. So that’s what’s different about these technologies. And when it comes to artificial intelligence, and we have some experts in the room, what’s different is not that we are dealing with something that’s beyond the current paradigm of computer science, of dealing with information in zeros and ones, but it’s just a different way of putting data, outcomes, and code together. So, imagine in the past, we used a code with data to get to some outcomes. But with artificial intelligence the outcome is that it comes together with data to determine the code which becomes a model, which can then interact with new datasets to come up with insights. So, it’s an interesting reversal of the earlier paradigm, at least with the current generation of artificial intelligence technologies. And this is where the power lies. You can deal with datasets that are simply impossible for humans to deal with. So, if you look at financial transactions in today’s markets, the speed, the volume and the shared variety of data that’s out there, it’s impossible for either humans or traditional computing systems to handle. So, you have to rely on artificial intelligence. So that’s the source of their power. And we’ve seen this power demonstrated first in the marketplace. Companies, such as Google and Meta, look at our data across a variety of devices across platforms and are able to get insights from that and place ads or other proposals before us that they capture our attention. There are actions and entire business models with huge market capitalization which have been created on that basis. The power of these technologies is seeping into other domains as well. Take Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems where AIS comes in to help select targets to go through petabytes data whether it’s coming from video feeds from drones or something else or multitude of sensors in the battle space can then help what planners decide which target to engage in and how. So, when conflict is taking place at warp speed, when you have a battlefield that is confusing to say the least and when you don’t have the kind of connectivity that you have been used to from the battlefield of the past. Then AI steps to select targets. Sometimes it allows them to make autonomous decisions about life and death, an issue that the U.N Secretary General is very, very concerned about and has stated quite early on that we should not allow machines to make decisions on their own to take life or inflict pain. Humans should remain accountable, should remain responsible for those decisions and the application of international humanitarian law, international national human rights law should not be obstructed just because machines are capable of being delegated some of these functions by us. So, I just gave you a few examples to illustrate the power of these technologies. Yes, the potential for good is there. We see challenges today, such as the climate challenge, the green transition from a take, make and waste economy to a circular economy. All these challenges cannot be handled without data, without artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies. So, what we need to get to a place where we can get a handle on this, where we can prevent the misuse but at the same time maximize the opportunities for good, maximize the potential of these technologies to contribute to the international community’s sustainable development goals, those 17 goals, from Zero Hunger and no Poverty all the way to conserving our Global Commons. I think the first thing we need to do is to make sure that the opportunity space is democratized. Today you have close to 3 billion people who are not connected to the internet, and even those who are connected often cannot afford connectivity in a meaningful way. They connect to devices which give them only a narrow window onto the digital world. The content that’s available to them is not in their languages. It’s not meaningful. It’s not empowering enough. When it comes to data, those who are left out of the data economy are the ones who are contributing data. They do not benefit from data. And when it comes to AI, and its application that is at the junction of digital and other sciences, you see the divisions even more starkly. So, all of Africa contributes less than one percent to patents and research publications on digital health and AI. And within Africa, a single country contributes 75% of that. So this is the extent of the divide at the data and AI end when it comes to some countries. And, mind you, this is not limited to the developing countries alone. Even in richer countries, you see many countries getting left behind by the data and AI Revolution. So the digital divide is not only about internet connectivity, it extends all the way to data. And if we are not mindful about it today, if we don’t address it today, you will have a yawning gap between the haves and the have-nots in the future. So, a few people who design the algorithms would use data to maximize value for themselves. And this is not just a morally untenable position. It’s also practically dangerous. If you don’t have diversity, in terms of datasets in terms of contributions to our digital future, we are likely to be running more risks than we should. Just take the gender divide issue. If today, we have certain problems in the tech domain, just imagine if there have been more women designing these two technologies 20 years back. Would we have seen the same kind of business models today? I doubt very much. So, lack of diversity is the practical risk for assets, it’s not just a modelling question. The other thing that we need to get right if we want to maximize the opportunity and minimize misuse is governance. We have a live example today. The collapse of the FDX Empire, the Crypto exchange. So, when three Regulators coming from three different domains are asked what they were doing, the answer was an awkward silence because this thing actually fell between three stools. And you cannot just say that, you know, these are offshore companies and laws of the land do not extend there. If the law of one of the most powerful countries on the planet cannot extend to these business models, you can imagine what might be happening elsewhere. So, at the national level, we have this ambiguity. We have the base of technology, this famous pacing problem between tech and policy, where regulators are using 19th century tools or 20th century mindsets to deal with some of these issues at the international level just as these things fall between schools in the national domains. Internationally they just fall at the borders because we are not used to cooperating on digital Technologies. And increasingly there’s a nationalist tone on these technologies from supply chains to manufacturing chips. And it’s not just an East West tissue. Even within the West, you see a competition between the EU and the US and sometimes even within Europe. So, there is a degree of beggar thy neighbour nationalist positions and these are preventing international cooperation on the governance of these technologies.

And then, in terms of our mindsets, what we learned today is lifecycle approaches to these technologies. Because you simply cannot at one point say “I will now sit back and just deal with some compliance issues.” Because what you see is data coming out of certain contexts, contributing to the AI models, the models then coming out with certain outcomes in that particular context. And what is developed inside the sandbox when it scales and is taken to society at large or the marketplace at large sometimes has a different impact than what it had in the original sandbox. So, unless you have a lifecycle approach, unless you look all the way from the context to the data, training data to the AI systems, and to their impact, you cannot handle their implications.

So some governments and some market regulators are looking at these issues. For instance, they are looking at smart regulation that combines competition policy and consumerism to deal with these issues. They are looking at getting together in the industry and getting together with civil society and academia to have more of a joint approach. But this is something that is very patchy at this point in time and needs to be done in a more coordinated manner. Otherwise, we will lose the trust of the public in technologies, and without trust we will not be able to scale, we would not be able to have the kind of digital transformation that we wish for.

I think we have an interactive session planned, so I’d like to end my remarks by speaking a little bit about a process that has started at the United Nations. A few years back, Secretary General Antonio Guterres, who has a deep interest in technology, and is actually a former student of this discipline, started a discussion around digital cooperation. He felt that there was insufficient cooperation across domains. Sometimes the tech issue is just discussed by technologists. We don’t have enough social scientists in the room, ethicists, designers, artists, poets, people with a different perspective. At the end of the day, it’s humans we are speaking about so it’s not just code. And he also felt that there was insufficient cooperation across borders, so he started a discussion on digital cooperation. And that discussion is now moving into a digital commons discussion just as we’ve had other global commons in the past, such as the maritime domain where the seas have been regulated, either through customary international law, or instruments such as the UN Convention on the Law of The Sea, or the outer space domain where outer space is supposed to be the province of all mankind and there are specific conventions that regulate how you send astronauts up in space or how you recover objects that fall toward the earth. So just like those models , the digital domain itself can be treated as the commons.

There are pirates and buccaneers who take advantage of opportunities , who indulge in ransomware , exploitation of children on the dark web and many other abuses. Therefore, we need guardians; we need certain rules of the road for these commons. And just like in the past, some of these commons were turned into private clubs and so they’re not truly commons available to the community. We face a similar problem today with the digital domain, the exclusion of democratic opportunity from everyone. So, we need guardrails for the digital commons. And the Secretary General has called for a “Summit of the Future” in 2024, at which one of the six key topics would be the digital commons. And a proposal has been made for a global digital compact, a kind of charter if you will, that brings us together; that helps us address this problem of things falling between stools or things stopping at borders. And not enough coordination, not enough alignment on approaches to digital technologies across borders.

The General Assembly of the Member States of the United Nations will need to come together to approve that proposal and the process has just started under the leadership of the Assembly President who has appointed two co-facilitators, the Permanent Representatives of Sweden and Rwanda, to lead that process. And my office has been entrusted with supporting them on this two-year journey to the global digital compact. A very important aspect of this journey is that it’s a multi-stakeholder journey even though these discussions will come to a conclusion at the summit of the future which is an intergovernmental process. The digital domain is multi-stakeholder so the private sector, academia, civil society and technological innovators have to contribute and have to be also part of the implementation of the global digital compact. It’s not enough for governments alone to agree on this and then apply it in their own practice. This has to be landed in the practice of the private sector as well. There is a consultation phase that we have just embarked on and these consultations have to be diverse; have to be inclusive. I was in Malta recently where nearly 100 people of different ages and different backgrounds came together for a very interesting, very insightful conversation. I go to Ethiopia next week, We must bring in new and emerging geographies of innovation in Africa, Asia and Latin America, and they have to be part of the conversation. Civil Society partners have come together to run their own consultation processes with the disabled, with women, with LGBTQ communities and others who often don’t get a voice when it comes to these intergovernmental negotiations. So, I would like to invite you today to bring forward some interesting ideas and contribute to this process, and host your own consultations. If you can, work with us so that we leave no voice behind; so that we can work together for an open, free, secure and inclusive digital future—— for all.”